Imprescindibles

Ficción

No Ficción

Ciencias y tecnología Biología Ciencias Ciencias naturales Divulgación científica Informática Ingeniería Matemáticas Medicina Salud y dietas Filología Biblioteconomía Estudios filológicos Estudios lingüísticos Estudios literarios Historia y crítica de la Literatura

Humanidades Autoayuda y espiritualidad Ciencias humanas Derecho Economía y Empresa Psicología y Pedagogía Filosofía Sociología Historia Arqueología Biografías Historia de España Historia Universal Historia por países

Infantil

Juvenil

#Jóvenes lectores Narrativa juvenil Clásicos adaptados Libros Wattpad Libros Booktok Libros de influencers Libros de Youtubers Libros Spicy Juveniles Libros LGTBIQ+ Temas sociales Libros ciencia ficción Libros de acción y aventura Cómic y manga juvenil Cómic juvenil Manga Shonen Manga Shojo Autores destacados Jennifer L. Armentrout Eloy Moreno Nerea Llanes Hannah Nicole Maehrer

Libros de fantasía Cozy Fantasy Dark academia Hadas y Fae Romantasy Royal Fantasy Urban Fantasy Vampiros y hombres lobo Otros Misterio y terror Cozy mistery Policiaca Spooky Terror Thriller y suspense Otros

Libros románticos y de amor Dark Romance Clean Romance Cowboy Romance Mafia y amor Romance dramatico Romcom libros Sport Romance Otros Clichés Enemies to Lovers Friends to Lovers Hermanastros Slow Burn Fake Dating Triángulo amoroso

Cómic y manga

Novela gráfica Novela gráfica americana Novela gráfica europea Novela gráfica de otros países Personajes, series y sagas Series y sagas Star Wars Superhéroes Cómics DC Cómics Marvel Cómics otros superhéroes Cómics Valiant

eBooks

Literatura Contemporánea Narrativa fantástica Novela de ciencia ficción Novela de terror Novela histórica Novela negra Novela romántica y erótica Juvenil Más de 13 años Más de 15 años Infantil eBooks infantiles

Humanidades Autoayuda y espiritualidad Ciencias humanas Economía y Empresa Psicología y Pedagogía Filosofía Historia Historia de España Historia Universal Arte Cine Música Historia del arte

Ciencia y tecnología Ciencias naturales Divulgación científica Medicina Salud y dietas Filología Estudios lingüísticos Estudios literarios Historia y crítica de la Literatura Estilo de vida Cocina Guías de viaje Ocio y deportes

WALTER REID

Recibe novedades de WALTER REID directamente en tu email

Filtros

Del 1 al 7 de 7

Birlinn 9780857909411

On 21 March 1918 Germany initiated one of the most ferocious and offensives of the First World War. During the so-called Kaiserschlacht, German troops advanced on allied positions in a series of ferocious attacks which caused massive casualties, separated British and French forces and drove the British back towards the Channel ports. Five days later, as the German advance continued, one of the most dramatic summits of the war took place in Doullens. The outcome was to have extraordinary consequences. For the first time an allied supreme commander the French General Foch was appointed to command all the allied armies, while the statesmen realized that unity of purpose rather than national interest was ultimately the key to success. Within a few months a policy of defence became one of offence, and paved the way for British success at Amiens and the series of unbroken British victories that led Germany to plea for armistice. Victory in November 1918 was a matter for celebration; what was excised from history was how close Britain was to ignominious defeat just eight months earlier.

Ver más

eBook

Birlinn 9780857909008

In 1947, when India achieved independence, Britain portrayed the transfer of power as the outcome of decades, even centuries, of responsible planning the honourable discharge of an historic responsibility. That view has never been seriously challenged in Britain. But this book shows that the official narrative is a travesty of what really happened.Drawing on the documentary evidence letters, diaries, state papers Walter Reid reveals how Britain selfishly deceived and prevaricated in order to arrest political progress in India for as long as possible a shameful passage in British imperial policy which led to tragedy and untold suffering when independence finally became inevitable.

Ver más

eBook

Birlinn 9781788854825

Neville Chamberlain is remembered today as Hitlers credulous dupe, the man who proclaimed in September 1938 that the Munich agreement guaranteed peace in our time.This is a magisterial reappraisal of Chamberlain and his legacy. It reveals the nuances of a complex and sensitive man who was a true radical and a man of passion, especially in all that concerned the welfare of his fellow citizens. As Minister of Health, Chancellor and Prime Minister, he presided over a fundamental modernisation of Britain, shuttingthe door on the Victorian age, ending free trade, improving living conditions and abolishing the Poor Law and the workhouse.Munich was much more than the traditional narrative suggests. Scarred by the death of his cousin in the First World War, Chamberlain was determined to ensure that a new generation was spared the tragic waste that had consumed their elders. Even so, he prepared for war while he worked for peace. The aircraft that won the Battle of Britain were built on his watch. He didnt win the Second World War, but it was he who ensured it wasnt lost in 1940.

Ver más

eBook

Birlinn 9780857901262

In 1940, after Dunkirk and the Battle of Britain, it could be seen that immediate and ignominious defeat by Nazi Germany had been averted. But victory seemed improbable. Relations with those whom Churchill had to work with against the Nazi threat were far from easy.He had to battle with his generals, Tory backbenchers and the War Cabinet, de Gaulle and the Free French, and - above all - the Americans.Walter Reid, bestselling author of Douglas Haig, Architect of Victory, reveals how much time and energy Churchill devoted to fighting the war that was excluded from the official accounts: the war with his allies.Recommended to all students of the high strategy of the Second World War without reservation - The British Army Review

Ver más

eBook

Birlinn 9780857901248

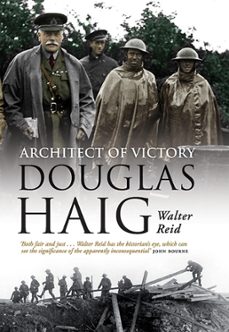

Douglas Haigs popular image as an unimaginative butcher is unenviable and unmerited. In fact, he masterminded a British-led victory over a continental opponent on a scale that has never been matched before or since. Contrary to myth, Haig was not a cavalry-obsessed, blinkered conservative, as satirised in Oh! What a Lovely War and Blackadder Goes Forth. Fascinated by technology, he pressed for the use of tanks, enthusiastically embraced air power, and encouraged the use of new techniques involving artillery and machine-guns. Above all, he presided over a change in infantry tactics from almost total reliance on the rifle towards all-arms, multi-weapons techniques that formed the basis of British army tactics until the 1970s. Prior re-evaluations of Haigs achievements have largely been limited to monographs and specialist writings.Walter Reid has written the first biography of Haig that takes into account modern military scholarship, giving a more rounded picture of the private man than has previously been available. What emerges is a picture of a comprehensible human being, not necessarily particularly likeable, but honourably ambitious, able and intelligent, and the man more than any other responsible for delivering victory in 1918.

Ver más

eBook

Birlinn 9780857900807

At the end of the First World War Britain and to a much lesser extent France created the modern Middle East. The possessions of the former Ottoman Empire were carved up with scant regard for the wishes of those who lived there. Frontiers were devised and alien dynasties imposed on the populations as arbitrarily as in medieval times.From the outset the project was destined to failure. Conflicting and ambiguous promises had been made to the Arabs during the war but were not honoured. Brief hopes for Arab unity were dashed, and a harsh belief in western perfidy persists to the present day. Britain was quick to see the riches promised by the black pools of oil that lay on the ground around Baghdad. When France too grasped their importance, bitter differences opened up and the area became the focus of a return to traditional enmity. The war-time allies came close to blows and then drifted apart, leaving a vacuum of which Hitler took advantage.Working from both primary and secondary sources, Walter Reid explores Britains role in the creation of the modern Middle East and the rise of Zionism from the early years of the twentieth century to 1948, when Britain handed over Palestine to UN control. From the decisions that Britain made has flowed much of the instability of the region and of the world-wide tensions that threaten the twenty-first century. How far was Britain to blame?

Ver más

eBook

Birlinn 9780857900555

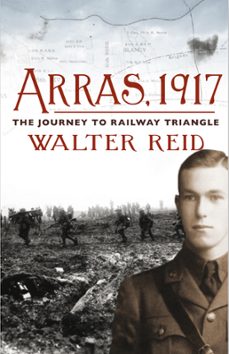

Arras, 1917 is a biography of the authors uncle, Ernest Reid, who died in 1917, an officer in the Black Watch, of wounds sustained in the Battle of Arras. Born and raised in Paisley, educated at Paisley Grammar School, then Glasgow University, Ernest Reid intended to become a lawyer before he volunteered for war service. The author the climate in which he grew up, and the influences which formed him and his generation, the generation which supplied the subalterns of the Great War. As a result, although the book remains primarily a biography of its subject, it also explored the spirit in which Britain, still essentially Victorian, went to war in 1914.This is the true and poignant account of a young Scottish officer, pinned down and fatally wounded in No-mans land on the first day of the Battle of Arras, on Easter Monday 1917. The gripping narrative creates a mood of sombre inevitability. It does not simply set out the events of Captain Ernest Reids life, but puts Ernests life into its moral as well as its historical context and describes the cultural influences - the code of duty, an unquestioning patriotism - that moulded him and his contemporaries for service and sacrifice in the killing fields of France and Flanders.In retrospect, he and they seem almost programmed for the role they were required to play, and in this lies the pathos at the heart of this moving book.

Ver más

eBook

Del 1 al 7 de 7